Beware of Greeks bearing gifts: the Laocoön group

- Cindy Levesque

- Nov 14, 2022

- 4 min read

Updated: Nov 26, 2022

The Trojan War

On the shores near Troy, after a decade of war, one day the Greeks simply packed up and left. They loaded up on their boats and sailed away. Just like that, a decade of fighting was over. No notes, no negotiations, just one thing: a large wooden horse. This was certainly confusing. The patron god of Troy was Poseidon whose favored animal was the horse. Clearly this horse was meant as a tribute to the god Poseidon, but why leave it there for the Trojans? As the Trojans were debating what to do with it, the idea of bringing it into the city was raised. Several were against this idea, but one man in particular was outright against it: Laocoon, the priest. The man was adamantly against bringing in the wooden horse, he started listing several reasons why this was a terrible idea as he walked into the water, flanked by his two sons. With the water going up to his knees, he continued his rant on why they should just burn the damned thing. As the crowd of men listened to him, they started to agree, he was right, they should just burn it. To emphasize his point, Laocoon threw a spear at the horse. Unfortunately, he did not notice the expression on the crowd’s face change from agreement to horror. For as Laocoon was speaking, with his back turned to the sea, sea serpents came forth. As the snakes’ heads were coiling up, they struck in unison. Laocoon and his two sons were caught, the snakes coiled around them and dragged them back into the sea. Poseidon had spoken. The Trojans now knew exactly what Poseidon wanted them to do, and they had no choice. The wooden horse would be taken into the city.

This powerful moment within the story of the Trojan War shows the exact moment that the Trojans were abandoned by their god Poseidon.

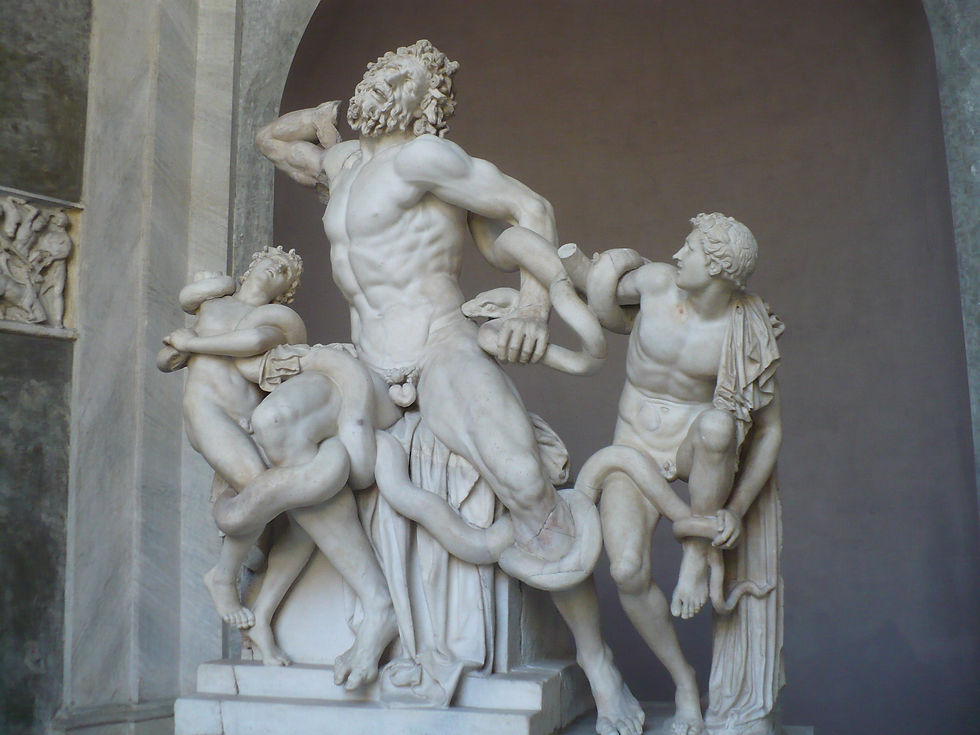

It is also no surprise that this exact moment would be recreated in glorious marble sculpture in a piece known as the Laocoon Group. Today it can be found in the Vatican Museum.

The original piece was created in the typical Hellenistic style; it had an overall pyramidal shape (a large base as the focus of the piece comes up to a point high in the middle) and the viewer was meant to walk around it to fully appreciate the piece. The original sculptors are believed to be Hagesandros, Athenedoros, and Polydoros of Rhodes. The statue was described by Pliny when he saw it in Emperor Titus’ palace. The sculptors had done their work from a single block of marble. Unfortunately, at some point in its history, someone decided that the piece was taking up too much space and tried to flatten it against a wall.

Heathens, scoundrels, and people who think history is boring have made multiple changes to the statue over the years. One of the sons was moved 90 degrees towards the front (breaking the snake, and the pyramidal shape). The right arms were removed and by the end, the single block of marble became seven blocks of marble.

From the Emperor’s palace, the piece would find its way to Nero’s Golden House and then be “lost” until it was rediscovered by Michelangelo (and others with him) in 1506. At this point, some of the limbs were outright missing. They brought what was left to the Belvedere Courtyard where it remained until being moved to the Vatican Museum. Over the years, some attempts have been made to restore it, though that remains a huge challenge even today. As bits and pieces (mostly right arms) have been found over the years, scholars have been able to study the anatomy to predict where the limbs were bent or extended.

The master sculptors, Hagesandros, Athenedoros, and Polydoros of Rhodes were also responsible for other sculptures depicting various scenes from Homer’s Odyssey. Some of them were found in Tiberius’ Grotto in Sperlonga. Odysseus and Achilles depict Odysseus dragging Achilles’ corpse away from the walls of Troy and the battlefield. The Palladium Group has Odysseus fail to steal Diomedes’ Palladium.

The Polyphemus Group shows Odysseus and his men holding the stake about to blind the man-eating Cyclops, Polyphemus, in order to escape the cave. The Scylla Group on the other hand portrays Scylla, a dog-like monster with twelve feet and six heads. When Odysseus and his men sailed too close to her, she leaned over and grabbed a sailor with each mouth and devoured them.

Archaeologists have found that the Laocoon Group, as well as the sculptures from Tiberius’ grotto were all made of the same marble (possibly from Asia Minor) and came from the same workshop. The Laocoon was probably only created a few years before or after the other groups. Because we don’t know the exact years that Hagesandros, Athenedoros and Polydoros lived, an exact date still can’t be set for the Laocoon.

Text: Cindy G Levesque. MENAM Archaeology. Copyright 2022.

Image: Cindy G Levesque.

Further Reading

Graves, R., 1964. The Greek Myths: 2. Penguin Books.

Howard, S., 1959. On the Reconstruction of the Vatican Laocoon Group. American Journal of Archaeology, Oct., 63(4), pp. 365-369.

Howard, S., 1989. Laocoon Rerestored. American Journal of Archaeology, Jul., 93(3), pp. 417-422.

Lynch, J. P., 1980. Laocoon and Sinon: Virgil, 'Aeneid' 2.40-198. Greece and Rome, Oct., 27(2), pp. 170-179.

Martin, J. R., 1968. Two Terra-Cotta Replicas of the Laocoon Group. Record of the Art Museum, Princeton University, 27(2), pp. 68-71.

Pedley, J. G., 2007. Greek Art and Archaeology. 4th Edition ed. Pearson Education, Inc.

Pollitt, J. J., 1990. Art of Ancient Greece: Sources and Documents. 1st Edition ed. Cambridge University Press.

Stewart, A. F., 1977. To Entertain an Emperor: Sperlonga, Laokoon and Tiberius at the Dinner-Table. The Journal of Roman Studies, Volume 67, pp. 76-90.

Tracey, S. V., 1987. Laocoon's Guilt. The American Journal of Philology, Autumn, 108(3), pp. 451-454.

Virgil, 2003. The Aeneid. Penguin Classics.

Comments