Gemstones in Ancient Egypt: The History

- Christofer Ek

- Oct 23, 2022

- 3 min read

When the word ‘gemstone’ is mentioned, people cannot help but imagine a variety of polished stones on expensive-looking jewelry. If we were to go back in time to when the ancient Egyptians ruled over Egypt, the word ‘gemstone’ would have a completely different meaning. For them, semi-precious stones had a magical and religious significance that, through rituals, could not only connect them, but also allow them to converse with their deities.

The closest matching word for “gemstones” has been transliterated to ’3t (aat), which means “minerals”. ’3t could also be combined with other words to further explain what kind of stone or occupation someone was referring to. A stonemason, for example, could be written as ms-’3t, as they had an occupation that involved working with stones. But how did the ancient Egyptians know where to find these semi-precious stones and what kind of tools to use when extracting them?

While searching for sturdy building blocks used in construction work, gemstones were often found in the vicinity. It is not entirely known what kind of technology the Egyptians used to extract semi-precious stones, but it is believed that similar methods were used for both hard and soft stone types. To easier differentiate where in Egypt different types of minerals were excavated, Egyptologists categorized the hard and soft stones as either being extracted from mines or from quarries. “Hard” stones refer to igneous or metamorphic rocks such as flint, granite, and quartzite. These were extracted from quarries and have been marked with a triangle shape in the included picture. “Soft” stones refer to sedimentary rocks such as sandstone, limestone, and gypsum. These types of stones were extracted from mines and are marked with a star shape in the included picture.

Mohs scale of mineral hardness is used to identify the scratch resistance of various minerals. The scale goes between 1 and 10 and the higher the number, the harder it is to scratch a mineral’s surface. This is why the ancient Egyptians used stone tools rather than bronze and copper tools when extracting gemstones. Flint has a hardness of 7 on the Mohs scale, while bronze and copper only have a hardness of 3. The stone tools were however soon replaced when iron became a popular material during the Egyptian Late Period (664-332 BCE).

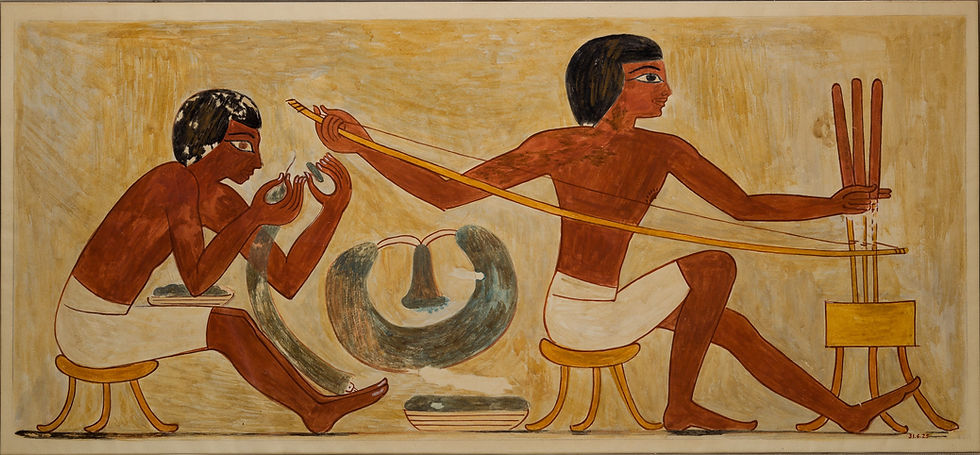

Gemstones were mostly used for jewelry, beads, amulets, and other small decorative items. The people who made these items were by society seen as great artisans, as it was no easy task to craft things out of brittle gemstones. During the crafting process, it was important that the artisan was aware of the gemstone's color, shape, and size. For example, amulets that represented a specific deity had to be of the correct color as even the slightest coloration change could alter its meaning completely. Red gemstones, like carnelian or jasper, signified blood, power, and chaos - while green gemstones, like malachite or turquoise, signified rebirth, fertility, and lush vegetation. To make sure that no mistakes were made, the artisans used sharp tools made from flint, unique-looking bow drills, and sandpaper made from silicide (SiO2) to smoothen the surface of the gems when they were completed. These tools and methods were used from the Early Dynastic Period (3000-2686 BCE) to the Roman Period (30 BCE - AD 395) when new techniques had been created and harder tools made from diamond and corundum were imported from India.

Text: Christoffer Ek. MENAM Archaeology. Copyright 2022.

Image credits:

Mohs Scale of Hardness - MENAM Archaeology. Copyright 2022. Map over mines & quarries - MENAM Archaeology. Copyright 2022.

Carnelian bead-manufacturing scene from tomb of Sobekhotep at Thebes, Dynasty 18. Photograph courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Further reading:

Bloxam, E. 2006 ‘Miners and Mistresses: Middle Kingdom mining on the margins’ JSA, vol 6

Bloxam, E. 2010 ‘Quarrying and Mining (Stone)’, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology

Harrel, J. 2012 ‘Gemstones’ UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology

Nicholson, P.T. & Shaw, I. 2000. Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology, Cambridge.

Comments