The Female nude in Mesopotamia: Identifying and understanding ancient women

- Olivia Berry

- Oct 23, 2022

- 5 min read

In the previous article of the Female Nude Series, we explored the issue of women within the archaeological record not being taken seriously as a legitimate field of research - until a few decades ago - and the women who helped pave the way.

Women would have made up roughly 50% of every society, so why are they difficult to find? For the vast majority of women in the ancient world, their narratives have been carved by men, for men, subsequently discovered by men who likely transmitted said narrative to what would have previously been an exclusively male audience - academic institutions. Fortunately, times have changed, where now our progressive, modern, western society is behind the widely spread activism on gender equality and women's rights, which encourages and stimulates an interest in the study of women in the past, and who they were.

Despite these recent triumphs, past thought and research still indoctrinate our current perceptions of how women in the ancient world were. This has been displayed through media representations of figures such as Cleopatra, who is often portrayed as a deviant, a dangerous seductress, who controls men through her sexuality. We have already established how women were perceived as the ‘other’ within their societies; however, Mesopotamian women would have possessed even more ‘otherness’ in their portrayal by later Greek and Roman scholars. Accounts from these historians, novelists and travellers characterise women as creatures of male power-fantasy, expressing and nurturing sensuality with no limitations. They were, in essence vapid and more importantly, willing.

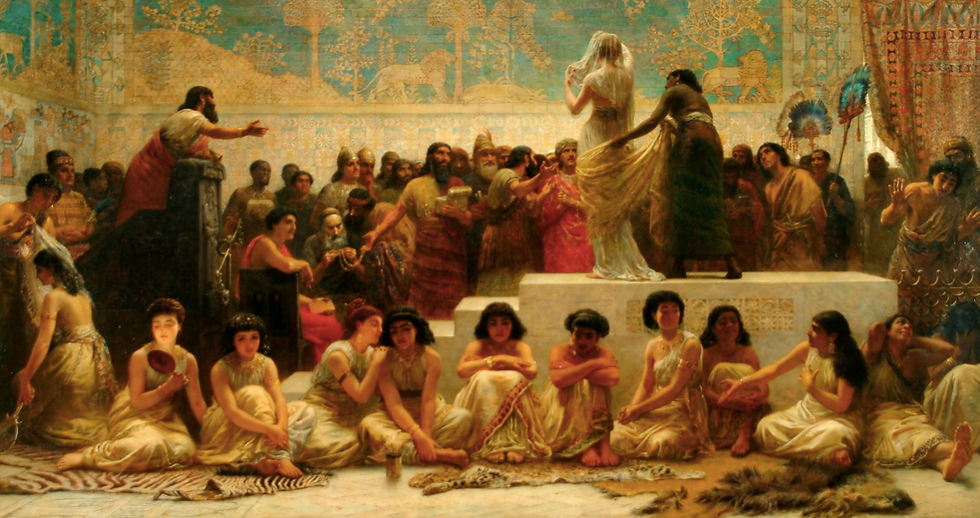

According to ancient Greek historian Herodotus, Mesopotamian (Babylonian, to be precise) women were obliged once in their lives, to commit a wholly shameful act of sitting in the temple of Aphrodite (or Ishtar) and giving themselves to a strange man. The women sit before the men, who have the power to choose any who takes his fancy; once he has chosen and thrown a silver coin into her lap, she has no choice or option to decline but must lay with him for her obligation to the goddess to terminate. Herodotus relays that the "ugly ones" sometimes have to wait three to four years before being chosen. Accounts such as this one set a precedent for how the rest of society viewed, and still view Mesopotamian women, and not without damage.

Textual evidence we have from Mesopotamia regarding women mostly reveals that they would have been members of elite families, often holding religious positions such as priestesses. The nadītu priestesses dedicated their lives to Shamash, the Babylonian sun god who resided in the city of Sippar, North of Babylon. The nadītu are an anomaly within the framework of Mesopotamian history; they were dominated by the men in society, perhaps more so than the other women, but were subsequently granted rights where they could manipulate and control the men in their own lives - mainly through inheritance and owning property. An interesting comparison are the nuns from the Middle Ages in England, daughters of high born men who lived in cloisters, some in their private quarters, where they had the freedom to deal with money and goods, interlacing their religious devotions with their business practices. Like the nadītu, they retreated from the world, which in return opened up other opportunities for them.

We know that in ancient Egypt the percentage of literate members of society was less than 1%; therefore, we can assume that the same percentage applied in Mesopotamia. We want to see the aspects of society that are not always easily accessible, and when facing the realisation that some of these aspects do not exist, or that they are simply hard to find, does not automatically mean that they would not have been considered important within society.

So where are all the ‘normal’ women?

Academics have argued for the idea that women belonging to the Old Akkadian Period did not have to live secluded lives, from the Queen to the ‘ordinary’ citizen, married or unmarried. They supposedly played an active role in public life on par with men and mingled freely with men. During the 4th and 3rd millennium BCE women had a decent coverage within the visual record, represented in glyptic art, luxury goods, statues and reliefs, however, images of this kind are not as standard when we come into the 2nd millennium BCE. Some believe that the 2nd millennium BC saw the decline of the social standing of women, or why their depictions in earlier centuries were so common.

Women’s work in the ancient Near East is a topic which is seldom discussed, but one with a substantial amount to offer. An occupation for ancient women did not always even require them to leave their private spheres. It has been suggested that domestic activities such as the preparation and production of food, cleaning, spinning and weaving would have demanded over 40 hours a week. If women were to take a job outside the home, it would likely have been a domestic role, which was merely an extension of their domestic activities. Women would have likely been the primary producers of textiles. Textiles and cloth were essential parts of life because they touched all aspects of social, political, economic and religious functions. Clothing can often act as one of the chief identifiers when determining rulers, high ranked individuals and even gender; displayed to us through the means of cylinder seals, statues and figurines. We know for example that individual members of Ur III society wore linen cloth which was reserved only for them. Textiles were perceived as emblems of status and in the realm of palaces and temples, such displays would reveal the level of prestige and wealth.

From surviving texts, we know that Mesopotamian kings, princes and rulers of vassal states traded luxurious textiles as gifts of alliance; cloth was offered as a gift to the gods and was also included in higher status dowries and marriage contracts. Some of these gifts and donations would have likely been made in textile workshops, although documents on the subject prove that most of the textile production would have been under temple administration and authorisation. Queen Shibtu of Mari had a workshop in the palace where hundreds of individuals worked; a smaller palace at Lagash held a workshop where large groups of virtually all-female workers were supervised - sometimes by a female leader - working long hours in a labour-intensive environment.

Interestingly, there are documents claiming that if a wife had domestic tools such as spindles and loom weights in her dowry (alongside their husband owning sheep), she essentially had her own textile business.

There is a lot that we don’t know about women’s occupations and roles within society, but it is clear just how crucial they were.

Text: Olivia Berry. MENAM Archaeology. Copyright 2022. Images:

The Babylonian Marriage Market painted by Edwin Long. 1875. (Royal Holloway, University of London)

Bust of Cleopatra. Wikkicommons.

Still from Cleopatra, 1963. Puzzle Factory.

Comments