The Female Nude IV: the role and progression of museums

- Olivia Berry

- Oct 24, 2022

- 4 min read

Welcome back to the Female Nude series!

In this article, we are getting down and dirty by analysing the role and progression of museums, directing their attention to how women are shown, from gallery displays to global exhibitions.

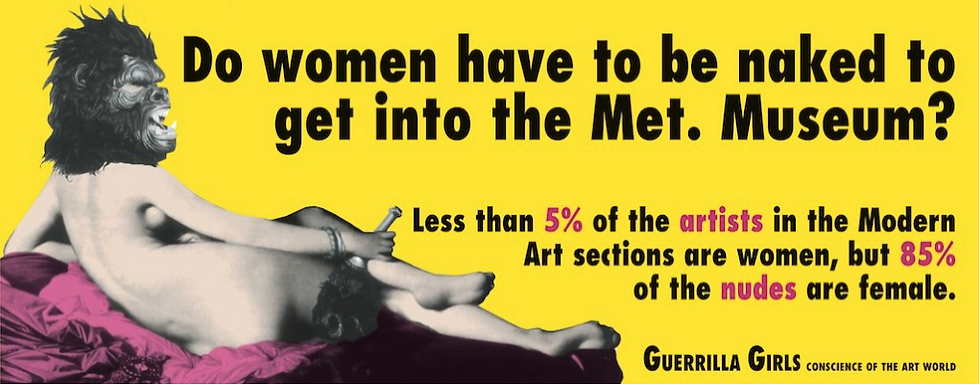

In 1989, the perception of women in institutions of cultural heritage and art galleries was revolutionised by the Guerrilla Girls, a group of women who inspected the modern art galleries in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. They explored the representation of female artists compared to the female subjects, where they found that less than 5% of the artists were women, yet 85% of the nudes were female. A question they presented to the curators - and, in essence, to the rest of the world - was via a giant billboard quoting: "Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum?." This slogan popularised the Guerrilla Girls and their activistic appeals. They released the same poster with updated statistics in 2005 and again in 2012, where 76% of nudes were female.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art has since put together multiple exhibitions celebrating and directing their attention on women. However, these exhibitions are not entirely representative of the average woman, ancient or modern. In 2016 they had exhibitions on Hatshepsut, Queen of Egypt; in 2010, ‘American Woman’ was launched focussing on female clothing; in 2011, ‘Mother India’, an exhibition on Indian goddesses; later, in 2016-2017 we see two art exhibitions displaying the works of female artists from India and France, which are more representative.

In 1991 the National Museum of American History assembled an exhibition titled Men and Women: A History of Costume, Gender, and Power and highlighted the different ways we view gender and power through ordinary objects used in daily life. Museums need to display invisible items such as cosmetic pots, spindles, storage vessels, and loom weights - all objects usually associated with women - and present them in a way that engages the audience. The idea of objects speaking for themselves needs to be rejected. Without the intervention of labels, the audience only sees what they have been taught to ignore - items relating to domesticity. However, such artefacts require more than the standard information label of one neutral sentence ascribed to the common museum object. The museum needs to intervene in a way which prevents visitors from leaving with the same view as when they first entered.

Developed out of an exhibition at the Whitworth Art Gallery in 1992 called Women and Men, art scholar Sarah Hyde extended its premise into book form. Exhibiting Gender includes several artworks, two at a time, ranging from sculptures, paintings and drawings, and asks the reader which is the work of women. After her fourth or fifth analysis, a clear pattern emerges. The artworks produced by men appear to have smoother edges and slicker, perfected bodily definitions as if to represent true femininity or the idea of the perfect nude form. The female artists, on the other hand, incorporate harsher outlines, the interpretations of the nude female form give the impression of more accurate representations, with asymmetrical breasts and the inclusion of pubic hair. It could be argued that these ‘real’ images of women by female artists are not only to be perceived as natural representations but that they also go against the patriarchal, heavily set concept behind what the perfect body appears to be. As well as this, we are subjected to other emotions that she can convey through canvas or stone, her usual pious, modest, complacent, or joyous manner swapped for the more unrefined anguished, lustful, angry and contemplative - emotions most often associated with men.

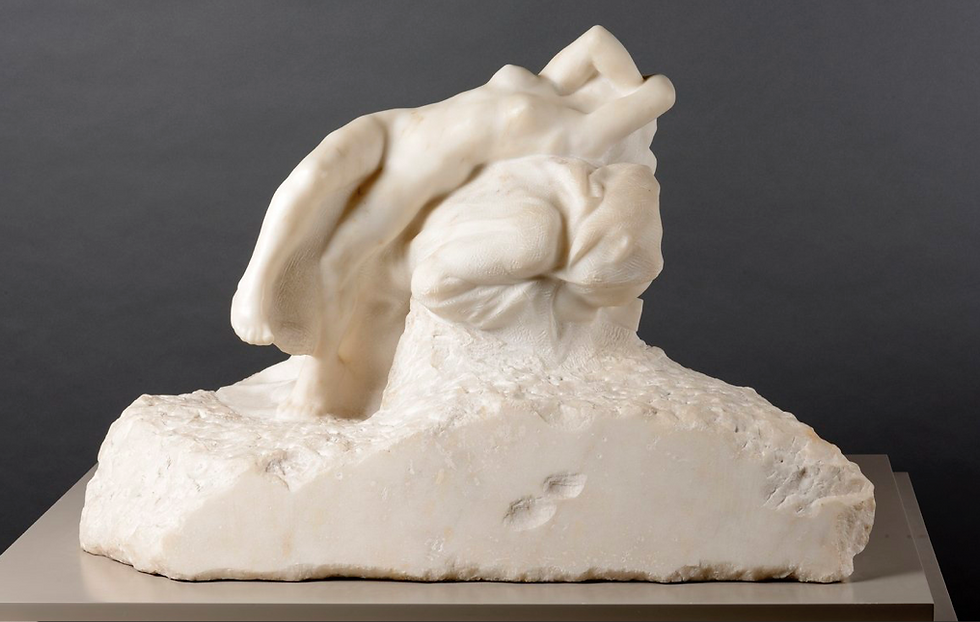

Returning to classical themes, in 2018, the British Museum held an exhibition titled Rodin and the Art of Ancient Greece. It included a large display of ancient Greek and Roman statues, as well as sculptures by Rodin, a well-known French artist and sculptor who took great inspiration from classical artists. A lot of the surrounding information was taken as direct quotes from Rodin, as well as museum curators. This information detailing statues of Aphrodite shows that the statues were seen through their sexual allure; with sentences mentioning “warm flesh”, and the bodies “eroticised by the clinging drapery”. The focal understandings of the exhibition were that women are represented as either docile, dependable mothers or homemakers, or eroticised through their nude form. The statues in the exhibition are very much set in their gender constructs, the representations of women are not displayed as thoughtful, inspiring, or powerful; whilst the representations of men, are not illustrated as docile, weak, emotional, or more importantly, sexual.

Over the past few years, we have seen a rush of female dominating exhibitions within the art and museum space, with the British Museum recently displaying a beautifully executed Feminine Power: the divine to the demonic, which showcased and celebrated the diversity and power of the divine woman. The National Gallery has also exhibited the works of Artemisia Gentileschi, who is so often known for her turbulent life, instead presenting her as the most acclaimed female artist of the 17th century. The visibility of women from the past is only growing stronger, but we need to remember to question what we believe is normal: so that we are left with the truth.

Text: Olivia Berry. MENAM Archaeology. Copyright 2022.

Further reading:

Clark, K. 1956. The Nude: A Study of Ideal Art. London: Penguin Books.

Clark Smith, B. 2010. A Woman’s Audience: A Case of Applied Feminist Theories. In: Levin, A, K. Gender, Sexuality and Museums: A Routledge Reader. Routledge.

Guerrilla Girls. 2018. https://www.guerrillagirls.com

Hyde, S. 1997. Exhibiting Gender. Manchester: Manchester University Press. Images: IMG 1: Guerrilla Girls Billboard. https://www.guerrillagirls.com/naked-through-the-ages

IMG 2: La Tentation de Saint Antoine by Auguste Rodin. Wiki Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:La_Tentation_de_Saint_Antoine_(face_3)_-_Auguste_Rodin_(B_661).jpg

Comments