False doors: gateways to the other world

- Josefin Percival

- Oct 24, 2022

- 3 min read

Without a doubt, any visitor to a museum with a larger Egyptian collection, or indeed to Egypt itself, has failed to notice the large stone pieces often labeled ‘false door’. These were common elements in ancient Egyptian tomb and temple architecture, but the style is not exclusive to Egypt. The design is strikingly similar to that of some Mesopotamian temples and the use of false doors seems to have traveled around the cultures and societies along the Mediterranean coast. First, let us look at the form and function of the false door as it was popularized in ancient Egypt.

False doors had a generalized appearance but went through some stylistic changes over time, which has made it possible for archaeologists to use the false doors as a means of dating tombs. Normally, they often feature a long and narrow ‘doorway’ in the center with a number of door jambs and columns inscribed with offering formulae. These formulae were for visitors to read out loud, an action which was equal to giving physical offerings. The outer frame would often resemble the gateway to a temple with a painted upper door jamb and larger pillars on either side.

The false door was a very popular feature during the Old Kingdom (ca. 2650-2150 BCE) and during the New Kingdom (ca. 1550-1070 BCE) when it seems to have had a revival. They were often, but not always, included in both private and royal tombs, as well as in temples and functioned as a sort of doorway between the world of the living and the world of the dead. Through them gods and goddesses, or the ka (the spirit of the dead) could travel between the two worlds. It was also a place where the dead could receive offerings from the living. As a result, a lot of false doors were painted or constructed in the tomb or temple where the dead could receive offerings from their living relatives. Offerings often consisted of food and drinks, indicated by the standard offering formula often including 1.000 jugs of hekhet (beer) and 1.000 loaves of t (bread). The false door in the tomb chamber was always situated on the western wall of the tomb, as the west symbolized the world of the dead and would mean direct interconnection, as if the tomb chamber was connected to the underworld as two rooms are connected by a door in a house.

So where did the false door come from?

Some archaeologists have proposed that Mesopotamian influence may have contributed to the style of the door since contact between Mesopotamia and Egypt during the 4th millennium BCE resulted in an exchange of both goods and stylistic trends. The Egyptian false doors closely resemble Mesopotamian temple architecture and it is believed that this borrowing came about through traveling workmen or sealings inscribed with temple decor.

Most Egyptologists have made a connection of the resemblance between the false doors and king Djoser’s mortuary complex in Saqqara in Egypt which was built in 2600 BCE, right before, or during, the emergence of the false doors. It is not unlikely that the standard design of the doors drew its stylistic inspiration from the mortuary complex in Saqqara.

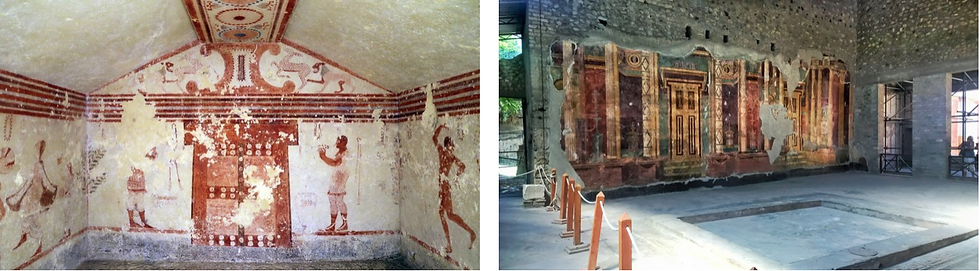

The use of false doors in tombs, either painted or sculpted, spread, and can for instance be found in Etruscan tombs from 550 BCE with the addition of humans painted on either side of the door. Later Roman false doors were rather used as a stylistic element in villas and some beautiful examples can be found in Pompeii.

Although we cannot say for sure where the original idea for the false doors came from, it is a reminder that ideas and cultures are constantly influencing each other and something that is often thought of as a typical feature of one culture may have had its origin somewhere completely different. It is in the exchange that cultures and societies are enriched.

Text: Josefin Percival. MENAM Archaeology. Copyright 2022.

Images: MENAM Archaeology, Ubisoft, and Wikimedia commons.

Further reading:

Bard K. A. 2015, An Introduction to the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt (2nd edition). Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Demand N. H. 2011, The Mediterranean context of Early Greek History. John Wiley & Sons.

Dodson A. 2010, ‘Mortuary Architecture and Decorative Systems’ in Lloyd A. A Companion to Ancient Egypt. Wiley-Blackwell.

Comments